About

Corpus of Texts Used

Included in my study are eighty-four poems written by Lord Byron between 1802 and 1821, as well as ninety-four poems written by Coleridge between 1787 and 1833. For this experiment, my indexing, analysis, and discussion are limited to the digital copies of Byron and Coleridge’s poetic works, all of which are edited by Ernest Hartley Coleridge, and are available to me through Project Gutenberg. Project Gutenberg offers seven volumes of Lord Byron’s poetry, though I have only used the first volume (1898), the second volume ( 1899), the third volume (1900), the fourth volume (1901), and the seventh volume (1904), as well as two volumes of Coleridge’s poetic works, though I have only used the first volume (1912). I chose these digital copies because they are open-access resources, meaning that I do not have to ask for or purchase permission to reproduce these texts in my own index, as well as for their availability as Plain Text Files, which can be copied and pasted into my TEI document with less formatting adjustments required than other formats.

The volumes that I have excluded from this study contain long dramatic poetic works, such as Byron’s Don Juan, and other non-poetic works. Dramatic works, although they could contain gendered personifications, the existence of multiple characters creates difficulty and confusion regarding matching the gendered pronoun or other gender indicators to the appropriate personification, whereas non-poetic works contain rare and infrequent instances of gendered personifications. Additionally, poems that do not contain at least one instance of gendered personifications are excluded from my corpus, as well as poems that are translations because I want to highlight Byron and Coleridge’s own gendering systems.

Indexing Methodology

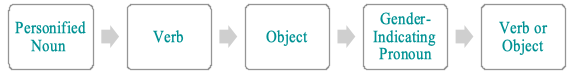

My indexing process involves reading through each poem in the aforementioned selected volumes to locate and manually note personifications that have a pronoun or other indicator that determines their gender; any poem that does not have any instances of gendered personifications is excluded from my index and study. While reading through the poems, I manually highlighted the personified noun and its gender indicator. Throughout this process, I found that most gendered personifications were fairly easy to identify, as many of them followed a common syntactic structure:

Consider this example from Coleridge’s “Qua Nocent Docent” where the speaker says, “No more, as then, should sloth around me throw/ her soul-enslaving, leaden chain!” (lines 2-3). As we can see clearly, grammatically, the pronoun “her” belongs to “sloth,” which grants it a feminine identity. In this example, because this instance of gendering appears within the first three lines of the poem, and no other nouns are personified within these first few lines, I can record this as an instance of gendered personifications with complete confidence. However, take this example from Byron’s “On the Death of a Young Lady, Cousin to the Author, and Very Dear to Him,” where the readers are introduced to Margaret (line 3), the poet’s cousin, who has died, in the first stanza of the poem. In the second stanza, however, Byron writes, “The King of Terrors seized her as his prey” (line 7). While this instance of gendered personifications follows a similar grammatical pattern as the first example, the personification of “death” is indirectly implied through the title “The King of Terrors.” From the context of the poem, I can tell that “her” is referring to Margaret, who has fallen “prey” to something, which the title and the first stanza indicate is “death”; therefore, I record this as an instance of a masculine personification as indicated by the word “King,” though in this instance, having a thorough knowledge of the context of the poem is necessary to make such a decision. As a result, I elected to not use the “search” or “find” functions, as a significant amount of reading is needed to understand the context of the poem in order to make an accurate decision regarding a potential instance of gendered personifications. Also, the “search” or “find” functions are not always effective in locating gendered personifications, as Byron and Coleridge assign gender in creative ways, such as through the use of words like “dictatress” (“English Bards and Scotch Reviewers line” 1003), that I might not have been able to anticipate, and therefore, would not know to look for these creative gender indicators.

Then, after I have manually compiled all the instances of gendered personifications in the works of the two poets, I copied the text of each poem from the Plain Text Files of the volumes from Project Gutenberg and pasted them into a T.E.I (Text Encoding Initiative) document using the program Oxygen XML Editor. At this stage, a significant amount of reformatting is needed to prepare the text for tagging, as I had to make a number of formatting changes, such as removing any underscores, as well as any letters, symbols, or numbers within the lines of the poems that were placed by Gutenberg editors as footnotes. To delete the underscores, I simply used the find and replace functions in Oxygen to locate the underscores and replace them with “nothing” by simply leaving the “replace” box empty. However, to remove any numbers and letters that are placed in square brackets all at once, I had to insert regular expressions into the search and find functions; these expressions were created by a programmer at Simon Fraser University’s DHIL. The following table summarizes the regular expressions that I used:

| Function | "Find" Field | Replace |

|---|---|---|

| To delete any numbers placed within squared brackets placed anywhere between the beginning and the end of a line. | \s*\[\d+\]\s* | *nothing* |

| To delete any Roman numerals placed within squared brackets placed anywhere between the start and end of a line. | \s*\[[ivxclm]+\]\s* | *nothing* |

| To delete any letters of the alphabet placed within squared brackets placed anywhere between the start and end of a line. | \s*\[[abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz]+\]\s* | *nothing* |

Without the ability to remove these underscores and footnote indicators, the process of preparing the text for tagging would have to be done manually, which is incredibly time consuming and creates room for errors. In addition to the regular expressions in the table, I also used the expression, ^\s*(.*?)\s*\d*s*$ in the “find” field, and <l>$1</l> in the “replace” field, to code each individual line of a poem as a “line.” Consider this example of Coleridge’s “Qua Nocent Docent” as it appears in the XML Editor file:

<div type="poem" xml:id="c3">

<head>

<title>Qua Nocent Docent</title>

</head>

<epigraph>

<quote>O! mihi praeteritos referat si Jupiter annos!</quote>

</epigraph>

<lg>

<l n="1">Oh! might my ill-past hours return again!</l>

<l n="2">No more, as then, should <seg ana="#sloth">sloth</seg>

around me throw</l>

<l n="3"><ref ana="#f" corresp="#sloth">Her</ref> soul-enslaving,

leaden chain!</l>

<l n="4">No more the precious time would I employ</l>

<l n="5">In giddy revels, or in thoughtless joy,</l>

<l n="6">A present joy producing future woe.</l>

</lg>

<lg>

<l n="7">But o'er the midnight Lamp I'd love to pore,</l>

<l n="8">I'd seek with care fair <seg ana="#learning">Learning</seg>'s

depths to sound,</l>

<l n="9">And gather scientific Lore:</l>

<l n="10">Or to mature the embryo thoughts inclin'd,</l>

<l n="11">That half-conceiv'd lay struggling in my mind,</l>

<l n="12">The cloisters' solitary gloom I'd round.</l>

</lg>

<lg>

<l n="13">'Tis vain to wish, for <seg ana="#time">Time</seg> has

ta'en <ref ana="#m" corresp="#time">his</ref> flight--</l>

<l n="14">For follies past be ceas'd the fruitless tears:</l>

<l n="15">Let follies past to future care incite.</l>

<l n="16">Averse maturer judgements to obey</l>

<l n="17"><seg ana="#youth">Youth</seg> owns, with pleasure owns,

the Passions' sway,</l>

<l n="18">But sage <seg ana="#experience">Experience</seg> only

comes with years.</l>

</lg>

</div>Here, the entire poem is encompassed with an open <div> and close </div> division tag that encodes this text as a single poem, as well as is assigned an id number – “c” refers to Coleridge, and “b” to Byron. Also, the title of the poem is surrounded by a beginning <head> and end </head> header tag, as well as an open <title> and close </title> title tag. Similarly, the epigraph is surrounded by an open <quote> and close </quote> tag and an open <epigraph> and close </epigraph>. epigraph tag. Next, each stanza is placed within a line group tag <lg> and </lg>, and each line is placed within a line tag <l> and </l>, as well as is given a line number (n=“#”). Because adding each individual line tag would be an exhaustive process, the aforementioned regular expression can automatically insert these tags all at once. Coding each segment of the text in this manner allows the oxygen program as well as the website platform that now hosts my index to understand each part of the text, which makes any necessary formatting or manipulating actions easier to carry out.

After the text has been prepared for tagging by removing the remnants of previous formatting and coding each segment of the text, I then tagged the gendered personifications.

In this example, we have five personified terms, “sloth,” “Learning,” “Youth,” “Experience,” and “Time,” though only “sloth” and “Time” are gendered. From these two examples, we can see how personification can be indicated through capitalization, as is the case for all of the personifications other than “sloth”–though not all personifications are capitalized, nor do all capitalizations denote personification, the capacity to possess physical features that are particular to living beings (i.e. wings), and the agency to feel emotions or preform actions (e.g. “tell”). All personifications are encoded as segments (“seg”) to indicate that they are personified. Terms that refer to a statue of a person, vague terms in terms of gender like the “spirit” and “muse,” and terms that are given qualities that are not necessarily exclusive to living beings, are not tagged as personifications. Finally, because “sloth” and “Time” are the terms that are gendered, they have been connected to the referents (“ref”) “her,” which is itself categorized as “#f” to denote feminization, and “his,” which is tagged as “m” to indicate masculinity. Nouns that are personified but not gendered are not assigned a referent. After indexing all of the poems fit the criteria outline above, I extracted my data and preformed various analyses using the Tableau Desktop program.