About the Astley's

Philip Astley was born in Newcastle-under-Lyme. Staffordshire, c. 1742. In 1759, he joined Colonel Eliott's 15th Light Dragoons, and distinguished himself for his equestrian skills. Returning to England after military service, he married Patty Jones in 1765; she, too, was an equestrian performer. The Astley's son, John, born in 1767, followed in his parents' footsteps, becoming an accomplished trick rider before he was 5.

The Astley's opened a riding school in an area named Halfpenny Hatch in Lambeth in 1768. Philp Astley supplemented their income by working as an instructor to the gentry by performing trick riding. The first advertisement for Astley’s “ACTIVITY on HO[R]SEBACK,” published in the Gazetteer and Public Advertiser for 4 April, 1768, promises that “Near twenty different attitudes will be performed on one, two and three horses every evening during the summer season excepting Sundays.”

Phillip Astley

Astley was certainly not the first person to perform popular equestrian entertainments for money, but he is acknowledged to be the first person to have had the idea of using an enclosed space where he could present his equestrian shows to a paying audience.

The early entertainments at Astley’s consisted largely of feats of horsemanship by men, women and by children -- but they also soon incorporated other novel acts such as acrobatics, automatons, bees swarming around their “trainer” in the shape of a wig, and tricks performed by the “Little Learned MILITARY HORSE.” Astley was particularly assiduous to assure the comfort of the nobility at his venue. A 1772 advertisement indicates that “Mr. ASTLEY has been at a very great Expence [sic] in making Preparations for the General Nights, in Order to accommodate the Nobility in an elegant manner, therefore flatters himself, the Variety and Drollness of the several Exhibitions cannot fail of giving the greatest Satisfaction to every Beholder, as there never was a Performance of its Kind at One Place in Europe.” In addition, he “humbly” requests that “the Nobility will be in good Time, in order to see the whole general Display” and suggests that he himself will greet the servants who arrive at four o’clock and will help them secure “such Places as they shall request.” The appearance of gentry at the circus performances also gave Astley as opportunity to advertise his riding lessons, as notices in the newspapers frequently indicate that “Ladies and Gentlemen are carefully instructed in all the rudiments of riding on horseback, six lessons one guinea, taken when convenient."

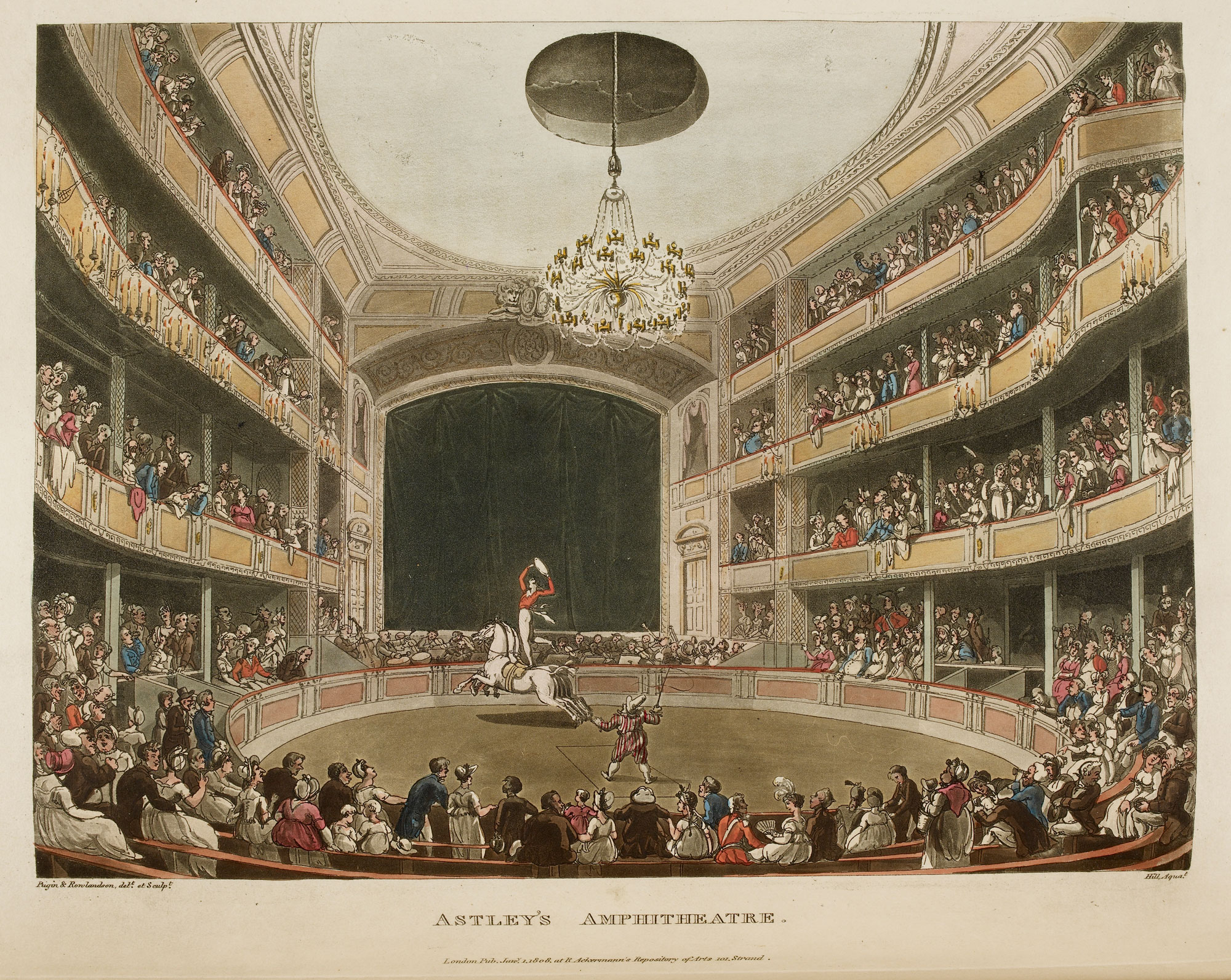

But, although Astley was anxious to “accommodate the Nobility,” his amphitheatre was also designed for a much wider audience, virtually anyone who could afford the price of entry. As a 1779 advertisement noted, “The many pleasing new entertainments which are now exhibiting at Astley’s Amphitheatre Riding-House, Westminster-bridge . . . have given universal applause to all ranks of spectators.”

Astley’s was site of sociability for all classes in Romantic-era London, albeit one that confirmed social hierarchy by providing special seats for the higher classes. Admittance at Astley’s was organized according to the following fees: “Box 2s. 6d. Upper Box 1s. 6d. Pit 1s. Gall[ery]. 6d.”

Astley was an astute businessman. With the profits from his popular shows, he was able to expand his enterprise over the next few years. He and his troupe performed in Dublin in 1773 and Paris in 1774, and they also played in the provincial areas of England.

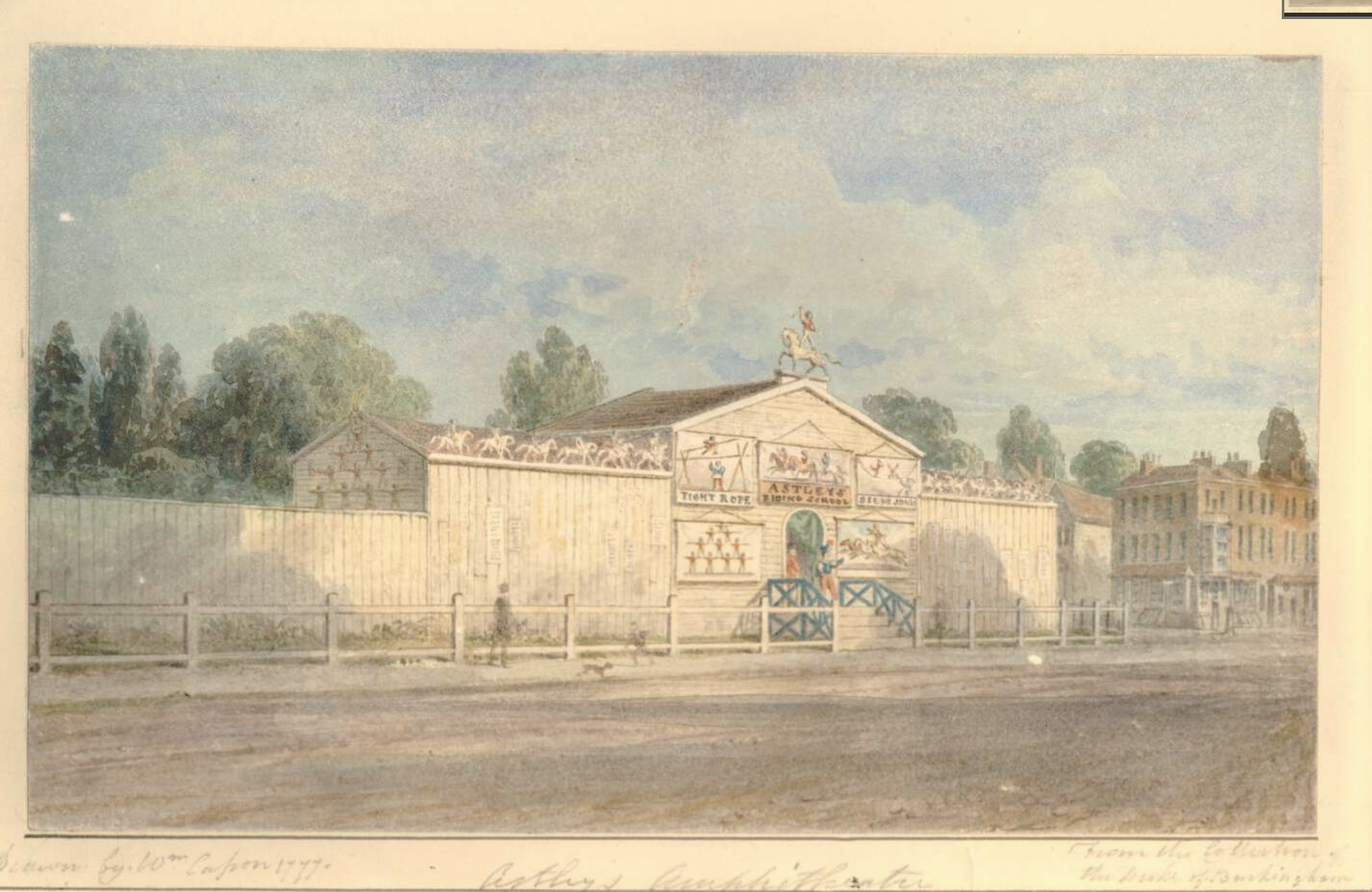

Exterior view of Astley's Amphitheatre, near Westminster Bridge; a sculpture of a man standing on top of a horse at top of entrance; posters and signs showing acrobatics across front. 1777 © The Trustees of the British Museum

In 1779, Astley’s moved to a better site on Westminster Bridge Road and added a roof and a stage to his amphitheatre. In 1786, he also established a permanent location in Paris at the Cirque du Palais Royal.

The growth of Astley’s entertainments correlates with what Richard Altick identifies as “an insatiable appetite for novelty” in the late eighteenth century that was “stimulated in part by the first stirrings of the mass communication industry” and that depended upon managers anticipating “what the public wanted at a given moment” [The Shows of London (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1978], 3.)

As the items in this database suggest, Astley was constantly changing the acts performed at his circus, drawing attention to what he imagined the public wanted at a given moment through his creative use of typography on his handbills and advertisements.

Astley’s success encouraged other entertainment entrepreneurs to try their hand at the circus business. Sites similar to Astley’s sprang up within London and other locations in the British archipelago as well as in Europe and North America, including Jones’s Equestrian Amphitheatre in Whitechapel (1786), Swan’s Amphitheatre in Birmingham (1787), the Edinburgh Equestrian Circus (1790), Ricketts's Equestrian Pantheon in Boston (1794) and Montreal (1797), and the Royal Circus, Equestrian and Philharmonic Academy in London (1782).

Astley’s made circus not just a London location of entertainment, but also a national and transnational phenomenon.